Back in the day we would enter program listings from magazines. That's how we got new utility and game software on a monthly basis. It was a fun activity in front of my Commodore Vic-20 on Saturdays.

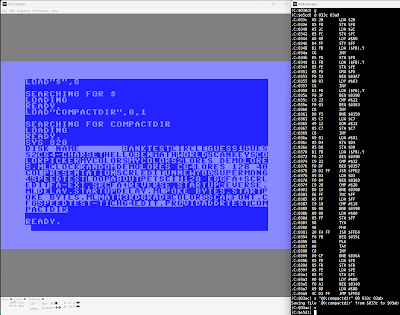

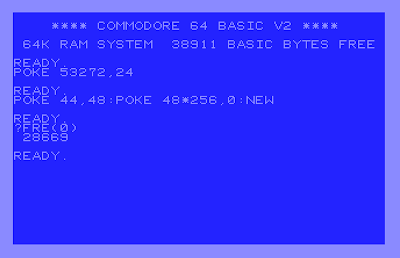

For nostalgia, and retro vibes, you can repeat the process to get this character editor program. It's online elsewhere and pointed to in this blog, but if you have an air gapped C64, you can enter directly.

Note: Floppy drive 8 is required for loading/saving fonts and theme configuration. This program does not support tape drives or alternate floppy drives. So be prepared with a floppy drive 8 such as 1541, 1571, 1581.

start: 0801

finish: 24b8

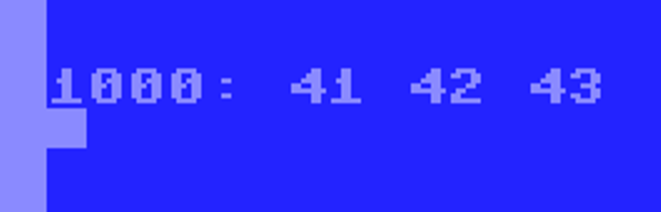

0801:0b 18 0a 00 9e 36 31 35 43

0809:37 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 b4

(gap of zeros or unused, use STOP+RESTORE if get stuck)

1800:00 0b 18 0a 00 9e 36 31 ae

1808:35 37 00 00 00 20 17 1f 6e

1810:18 66 a6 18 6e b1 24 a9 68

1818:00 85 22 a9 08 85 23 20 45

1820:a3 20 ad 18 d0 29 f0 8d fb

1828:b3 24 09 04 8d b4 24 20 44

1830:97 21 20 2b 20 a5 2c c9 e4

1838:18 f0 36 a9 01 a2 18 85 5a

1840:2b 86 2c a9 00 85 fb 85 5b

1848:fd a9 08 85 fc a2 d0 86 d5

1850:fe a9 10 85 ff a0 00 78 bf

1858:20 63 1f b1 fd 91 fb c8 67

1860:d0 f9 e6 fc e6 fe c6 ff e4

1868:d0 f1 20 5c 1f 58 20 7c 5e

1870:1f a9 93 20 d2 ff a9 13 0c

1878:20 d2 ff 2c b1 24 30 44 f2

1880:a9 a1 a2 22 20 8e 1d a9 83

1888:30 a2 23 85 b4 86 b5 20 81

1890:9f 1d 20 cc 1e a9 30 85 26

1898:fd a9 08 85 ff a9 be a2 52

18a0:23 20 8e 1d a5 fd 20 d2 46

18a8:ff a9 b3 a2 23 20 8e 1d b7

18b0:a9 20 20 d2 ff 20 9f 1d cb

18b8:e6 fd c6 ff d0 df 20 db d6

18c0:20 20 9f 1d 20 e1 1e a9 3d

18c8:00 85 27 a9 00 85 28 a9 e9

18d0:38 a2 04 85 29 86 2a a2 f8

18d8:d8 85 b2 86 b3 18 a5 a2 81

18e0:69 04 85 a3 20 b9 1d a0 74

18e8:00 b1 29 85 a7 ad 18 d0 f7

18f0:29 fe c9 10 d0 05 a9 12 af

18f8:8d 18 d0 20 8b 1e 20 e4 0c

1900:ff f0 ea 48 20 bb 1e 68 e4

1908:c9 4e d0 19 20 17 1f a5 9f

1910:22 69 07 85 22 90 c6 e6 ae

1918:23 a5 23 c9 10 90 be a9 30

1920:08 85 23 d0 b8 c9 2b d0 3d

1928:19 20 17 1f a5 22 69 7f cb

1930:85 22 90 a9 e6 23 a5 23 8c

1938:c9 10 90 a1 a9 08 85 23 1b

1940:d0 9b c9 42 d0 1a 20 17 65

1948:1f a5 22 e9 08 85 22 b0 a1

1950:8c c6 23 a5 23 c9 08 b0 3a

1958:84 a9 0f 85 23 4c dd 18 8f

1960:c9 2d d0 1a 20 17 1f a5 bf

1968:22 e9 80 85 22 b0 0c c6 41

1970:23 a5 23 c9 08 b0 04 a9 53

1978:0f 85 23 4c dd 18 c9 11 b0

1980:d0 31 a5 29 69 27 85 29 ca

1988:85 b2 90 05 e6 2a e6 b3 ed

1990:18 a5 28 69 01 29 07 85 14

1998:28 d0 15 38 a5 29 e9 40 1f

19a0:85 29 85 b2 a5 2a e9 01 66

19a8:85 2a a5 b3 e9 01 85 b3 2a

19b0:4c e7 18 c9 91 d0 33 a5 7e

19b8:29 e9 28 85 29 85 b2 b0 cc

19c0:05 c6 2a c6 b3 38 a5 28 ca

19c8:e9 01 29 07 85 28 c9 07 2d

19d0:d0 15 18 a5 29 69 40 85 03

19d8:29 85 b2 a5 2a 69 01 85 30

19e0:2a a5 b3 69 01 85 b3 4c 70

19e8:e7 18 c9 1d d0 1e e6 29 16

19f0:e6 b2 a5 27 69 00 85 27 e7

19f8:29 07 d0 0d 38 a5 29 e9 01

1a00:08 85 29 85 b2 a9 00 85 d8

1a08:27 4c e7 18 c9 9d d0 18 df

1a10:c6 29 c6 b2 c6 27 10 0d f5

1a18:18 a5 29 69 08 85 29 85 ab

1a20:b2 a9 07 85 27 4c e7 18 a3

1a28:c9 13 d0 17 a9 00 85 27 11

1a30:85 28 a9 38 85 29 85 b2 78

1a38:a9 04 85 2a a9 d8 85 b3 05

1a40:4c e7 18 c9 20 d0 11 20 ba

1a48:1e 1f a6 27 a4 28 b1 22 e5

1a50:5d 91 22 91 22 4c dd 18 0b

1a58:c9 03 d0 1b 20 f1 21 ad b6

1a60:b5 24 8d 18 d0 18 4e b1 e0

1a68:24 a9 d4 a2 23 20 8e 1d b1

1a70:20 cc 1e 20 e1 1e 60 c9 bf

1a78:53 d0 49 20 80 20 a9 93 21

1a80:20 d2 ff a9 0a 85 39 a9 96

1a88:00 85 3a a9 c0 85 9d a9 01

1a90:01 a2 08 a0 0f 20 ba ff 67

1a98:a9 0b a2 d6 a0 23 20 bd b5

1aa0:ff a9 00 85 fb a9 08 85 b3

1aa8:fc a9 fb a2 00 a0 18 20 42

1ab0:d8 ff a9 ec a2 23 20 8e c5

1ab8:1d 20 e4 ff f0 fb 20 96 6e

1ac0:20 4c 71 18 c9 93 d0 0f 15

1ac8:20 1e 1f a9 00 a0 07 91 35

1ad0:22 88 10 fb 4c dd 18 c9 cd

1ad8:12 d0 11 20 1e 1f a0 07 24

1ae0:b1 22 49 ff 91 22 88 10 d5

1ae8:f7 4c dd 18 c9 3c d0 10 5a

1af0:20 1e 1f a0 07 b1 22 0a f7

1af8:91 22 88 10 f8 4c dd 18 5d

1b00:c9 3e d0 10 20 1e 1f a0 1e

1b08:07 b1 22 4a 91 22 88 10 4d

1b10:f8 4c dd 18 c9 d6 d0 16 74

1b18:20 1e 1f a0 07 88 b1 22 b3

1b20:c8 91 22 88 10 f7 c8 a9 87

1b28:00 91 22 4c dd 18 c9 5e 0d

1b30:d0 18 20 1e 1f a2 07 a0 ec

1b38:00 c8 b1 22 88 91 22 c8 90

1b40:ca d0 f6 a9 00 91 22 4c 60

1b48:dd 18 c9 46 d0 25 20 1e 8a

1b50:1f a0 03 84 ff c8 84 fe 12

1b58:a4 ff b1 22 48 a4 fe b1 bd

1b60:22 aa 68 91 22 a4 ff 8a a6

1b68:91 22 e6 fe c6 ff 10 e8 fb

1b70:4c dd 18 c9 52 d0 25 20 24

1b78:1e 1f a0 00 a2 00 b1 22 34

1b80:0a 91 22 76 a8 e8 e0 08 7e

1b88:d0 f4 c8 c0 08 d0 ed a0 89

1b90:07 b9 a8 00 91 22 88 10 04

1b98:f8 4c dd 18 c9 4d d0 26 e6

1ba0:20 1e 1f a0 07 a2 07 b1 de

1ba8:22 4a 91 22 b9 a8 00 2a 71

1bb0:99 a8 00 ca 10 f1 88 10 f3

1bb8:ec a0 07 b9 a8 00 91 22 94

1bc0:88 10 f8 4c dd 18 c9 40 46

1bc8:d0 14 ad b5 24 cd b4 24 63

1bd0:f0 06 20 74 20 4c ed 18 72

1bd8:20 62 20 4c ed 18 c9 2a 0e

1be0:d0 2d ad aa 24 ae ad 24 86

1be8:ac af 24 8e aa 24 8c ad 7b

1bf0:24 8d af 24 ad a9 24 ae df

1bf8:ac 24 ac ae 24 8e a9 24 e1

1c00:8c ac 24 8d ae 24 20 a3 f0

1c08:20 20 cc 20 4c dd 18 c9 c7

1c10:5a d0 24 a6 a4 f0 1d a5 61

1c18:a5 d0 07 20 1e 1f c6 a4 d9

1c20:a6 a4 e6 a5 ca 86 a4 8a 50

1c28:20 4c 1f a0 07 b1 fb 91 f9

1c30:22 88 10 f9 4c dd 18 c9 11

1c38:43 d0 0f a0 07 b1 22 99 0f

1c40:51 02 88 10 f8 84 a6 4c 27

1c48:ed 18 c9 56 d0 14 24 a6 e1

1c50:10 0d 20 1e 1f a0 07 b9 fc

1c58:51 02 91 22 88 10 f8 4c d0

1c60:dd 18 c9 58 d0 16 20 1e 89

1c68:1f a0 07 b1 22 99 51 02 70

1c70:a9 00 91 22 88 10 f4 84 c4

1c78:a6 4c dd 18 c9 59 d0 0d b6

1c80:a5 a5 f0 09 c6 a5 e6 a4 e2

1c88:a6 a4 4c 27 1c c9 2f d0 70

1c90:32 20 17 1f a9 00 a2 08 59

1c98:85 fb 86 fc a2 10 85 fd 91

1ca0:86 fe a2 08 86 ff a0 00 26

1ca8:b1 fb aa b1 fd 91 fb 8a e1

1cb0:91 fd c8 d0 f3 e6 fc e6 73

1cb8:fe c6 ff d0 eb 20 7c 1f 27

1cc0:4c dd 18 c9 85 d0 16 ee c0

1cc8:86 02 ad 86 02 4d 21 d0 3b

1cd0:29 0f f0 f3 20 cc 1e 20 4f

1cd8:b9 1d 4c ed 18 c9 89 d0 69

1ce0:1b 18 ad a8 24 69 01 29 de

1ce8:0f 8d a8 24 ad 21 d0 4d 44

1cf0:a8 24 29 0f f0 eb 20 b9 cd

1cf8:1d 4c ed 18 c9 86 d0 10 2c

1d00:ee 21 d0 ad 21 d0 4d 86 5c

1d08:02 29 0f f0 f3 4c ed 18 43

1d10:c9 8a d0 10 ce 21 d0 ad 37

1d18:21 d0 4d 86 02 29 0f f0 ec

1d20:f3 4c ed 18 c9 87 d0 06 ba

1d28:ee 20 d0 4c ed 18 c9 8b af

1d30:d0 06 ce 20 d0 4c 38 1d 75

1d38:c9 88 d0 1b 18 ad a7 24 30

1d40:69 01 29 0f 8d a7 24 ad 86

1d48:21 d0 4d a7 24 29 0f f0 40

1d50:eb 20 b9 1d 4c ed 18 c9 a5

1d58:8c d0 11 18 ad a6 24 69 6a

1d60:01 29 0f 8d a6 24 20 b9 df

1d68:1d 4c ed 18 c9 48 d0 0b 9f

1d70:ad b1 24 49 80 8d b1 24 c8

1d78:4c 71 18 c9 30 90 0c c9 7a

1d80:3a b0 08 29 0f 20 eb 20 88

1d88:4c 76 18 4c ed 18 85 fb 25

1d90:86 fc a0 00 b1 fb f0 06 c6

1d98:20 d2 ff c8 d0 f6 60 a9 f0

1da0:cf a2 23 20 8e 1d a5 b4 ba

1da8:a6 b5 20 8e 1d c8 98 18 e5

1db0:65 b4 85 b4 90 02 e6 b5 d6

1db8:60 a9 38 a2 04 85 24 86 c3

1dc0:25 a2 d8 85 b0 86 b1 a9 56

1dc8:08 85 ff a0 00 a2 08 b1 be

1dd0:22 85 26 ad a6 24 91 b0 b6

1dd8:ad a9 24 06 26 90 08 ad 6a

1de0:a7 24 91 b0 ad aa 24 91 27

1de8:24 e6 24 e6 b0 d0 04 e6 99

1df0:25 e6 b1 ca d0 dd 18 a5 2e

1df8:24 69 1f 85 24 85 b0 90 05

1e00:04 e6 25 e6 b1 c8 c6 ff 49

1e08:d0 c3 2c b1 24 10 03 4c f1

1e10:e1 1e 20 6c 1f a2 19 86 cb

1e18:24 86 b0 a2 04 86 25 a2 6f

1e20:d8 86 b1 38 66 ff a0 00 98

1e28:20 65 1e e6 24 e6 b0 d0 ee

1e30:04 e6 25 e6 b1 18 66 ff f5

1e38:a2 08 18 a5 24 69 25 85 bb

1e40:24 85 b0 90 04 e6 25 e6 fb

1e48:b1 ad ab 24 2c b0 24 30 1d

1e50:02 a9 e5 91 24 e6 24 d0 a3

1e58:02 e6 25 b1 22 20 65 1e 89

1e60:c8 ca d0 d6 60 48 4a 4a 3e

1e68:4a 4a 20 7a 1e e6 24 e6 c3

1e70:b0 d0 04 e6 25 e6 b1 68 b8

1e78:29 0f 09 30 c9 3a 90 02 8b

1e80:e9 39 24 ff 10 02 09 80 9f

1e88:91 24 60 38 a5 a3 c5 a2 10

1e90:d0 28 a5 a2 69 1d 85 a3 8c

1e98:a0 00 ad a7 24 2c b0 24 ac

1ea0:10 0c b1 29 49 80 91 29 49

1ea8:ad a8 24 91 b2 60 b1 b2 b0

1eb0:29 0f cd a8 24 d0 f1 20 f1

1eb8:b4 20 60 a0 00 a5 a7 91 e4

1ec0:29 20 b4 20 18 a5 a2 69 38

1ec8:02 85 a3 60 a0 00 ad 86 c8

1ed0:02 99 00 d8 99 00 d9 99 1c

1ed8:00 da 99 00 db c8 d0 f1 94

1ee0:60 a9 b8 a2 05 85 fb 86 b5

1ee8:fc 2c b1 24 10 10 a0 00 29

1ef0:a9 20 91 fb c8 d0 fb 20 9d

1ef8:6c 1f a8 91 fb 60 20 0e 11

1f00:1f 2c b1 24 30 10 a9 d0 37

1f08:a2 06 85 fb 86 fc a0 00 f2

1f10:98 91 fb c8 d0 fa 60 a9 e7

1f18:00 85 a4 85 a5 60 a5 a4 43

1f20:c9 18 90 15 a2 00 a0 08 0b

1f28:b9 3c 03 9d 3c 03 e8 c8 15

1f30:c0 c4 d0 f4 a2 17 86 a4 8c

1f38:8a 20 4c 1f a0 07 b1 22 e5

1f40:91 fb 88 10 f9 e6 a4 c8 d5

1f48:84 a5 18 60 0a 0a 0a 18 df

1f50:69 3c 85 fb a2 03 90 01 06

1f58:e8 86 fc 60 a5 01 09 07 9c

1f60:85 01 60 a5 01 29 f8 09 af

1f68:03 85 01 60 a5 23 85 ff 74

1f70:a5 22 46 ff 6a 46 ff 6a a9

1f78:46 ff 6a 60 a9 00 a2 10 cf

1f80:85 fb 86 fc a2 38 85 fd 20

1f88:86 fe a2 08 86 ff a0 00 14

1f90:b1 fb 91 fd c8 d0 f9 e6 1d

1f98:fc e6 fe c6 ff d0 f1 60 e2

1fa0:2c 19 d0 30 03 4c 31 ea ee

1fa8:ad 19 d0 29 01 f0 f6 ad 18

1fb0:b2 24 10 2a ad 12 d0 c9 17

1fb8:c2 90 f9 a2 0a ca d0 fd 01

1fc0:ad b6 24 8d 18 d0 a9 00 38

1fc8:8d 12 d0 8d b2 24 ad 11 d7

1fd0:d0 29 7f 8d 11 d0 a9 01 aa

1fd8:8d 19 d0 4c 25 20 f0 2a b8

1fe0:ad 12 d0 c9 8a 90 f9 a2 5e

1fe8:0a ca d0 fd ad b5 24 8d f2

1ff0:18 d0 a9 a4 8d 12 d0 8d d2

1ff8:b2 24 ad 11 d0 29 7f 8d 18

2000:11 d0 a9 01 8d 19 d0 4c 01

2008:25 20 ad b4 24 8d 18 d0 3c

2010:a9 68 8d 12 d0 8d b2 24 58

2018:ad 11 d0 29 7f 8d 11 d0 45

2020:a9 01 8d 19 d0 68 a8 68 9a

2028:aa 68 40 78 a9 00 8d b2 82

2030:24 a9 00 8d 12 d0 ad 11 06

2038:d0 29 7f 8d 11 d0 ad 14 2f

2040:03 ae 15 03 e0 1f f0 10 f5

2048:8d a6 1f 8e a7 1f a9 a0 73

2050:a2 1f 8d 14 03 8e 15 03 1c

2058:ad 1a d0 09 01 8d 1a d0 e3

2060:58 60 ad b4 24 29 f0 09 96

2068:02 8d b5 24 29 f0 09 0e 33

2070:8d b6 24 60 ad b4 24 8d c5

2078:b5 24 09 02 8d b6 24 60 cd

2080:ad b5 24 8d b7 24 ad b6 c2

2088:24 8d b8 24 ad b4 24 8d ad

2090:b5 24 8d b6 24 60 ad b7 87

2098:24 8d b5 24 ad b8 24 8d 6d

20a0:b6 24 60 a9 80 8d b0 24 ab

20a8:ad aa 24 cd a9 24 d0 03 4e

20b0:4e b0 24 60 a4 28 b1 22 1a

20b8:a6 27 3d 91 22 c9 01 ad be

20c0:a6 24 90 03 ad a7 24 a0 94

20c8:00 91 b2 60 a9 24 a2 23 10

20d0:20 8e 1d 20 db 20 a9 92 af

20d8:4c d2 ff a9 ee a2 22 2c 01

20e0:b0 24 30 04 a9 09 a2 23 a2

20e8:4c 8e 1d c9 00 d0 02 a9 24

20f0:0a c9 0b 90 01 60 a8 a9 97

20f8:49 a2 24 85 fb 86 fc 88 df

2100:f0 0f 18 a5 fb 69 09 85 f8

2108:fb a5 fc 69 00 85 fc d0 c8

2110:ee a0 00 b1 fb 8d 86 02 32

2118:c8 b1 fb 8d 21 d0 c8 b1 13

2120:fb 8d 20 d0 c8 b1 fb 8d 67

2128:a6 24 c8 b1 fb 8d a7 24 84

2130:c8 b1 fb 8d a8 24 c8 b1 b4

2138:fb 8d a9 24 c8 b1 fb 8d e5

2140:aa 24 c8 b1 fb 8d ab 24 a6

2148:20 a3 20 20 cc 1e 4c 51 52

2150:21 ad aa 24 c9 a0 d0 13 ab

2158:a9 20 8d ac 24 a9 2a 8d 9d

2160:ad 24 a9 cf 8d ae 24 8d b1

2168:af 24 60 c9 2a d0 13 a9 98

2170:cf 8d ac 24 8d ad 24 a9 ea

2178:20 8d ae 24 a9 a0 8d af e0

2180:24 60 a9 20 8d ac 24 a9 35

2188:a0 8d ad 24 a9 20 8d ae 0e

2190:24 a9 2a 8d af 24 60 a9 e5

2198:fe a2 23 20 8e 1d 20 6d ff

21a0:22 d0 4d a9 0a 85 39 a9 ee

21a8:00 85 3a a9 c0 85 9d a9 2f

21b0:01 a2 08 a0 00 20 ba ff 1d

21b8:a9 08 a2 e4 a0 23 20 bd 04

21c0:ff a9 00 a2 b9 a0 24 20 50

21c8:d5 ff a2 09 a0 00 b9 b9 0d

21d0:24 99 a3 24 c8 ca d0 f6 4c

21d8:ad a3 24 ae a4 24 ac a5 fe

21e0:24 8d 86 02 8e 21 d0 8c b0

21e8:20 d0 20 a3 20 20 51 21 f2

21f0:60 ad 86 02 29 0f 8d a3 04

21f8:24 ad 21 d0 29 0f 8d a4 2f

2200:24 ad 20 d0 29 0f 8d a5 19

2208:24 20 5c 22 f0 4d 20 80 91

2210:20 a9 1f a2 24 20 8e 1d b8

2218:20 6d 22 d0 3e a9 0a 85 4b

2220:39 a9 00 85 3a a9 c0 85 43

2228:9d a9 01 a2 08 a0 0f 20 f0

2230:ba ff a9 0b a2 e1 a0 23 b8

2238:20 bd ff a9 a3 85 fb a9 6b

2240:24 85 fc a9 fb a2 ac a0 96

2248:24 20 d8 ff a9 ec a2 23 2b

2250:20 8e 1d 20 e4 ff f0 fb f2

2258:20 96 20 60 a2 09 a0 00 d6

2260:b9 b9 24 d9 a3 24 d0 04 65

2268:c8 ca d0 f4 60 20 e4 ff 7a

2270:f0 fb c9 4e d0 0b a9 45 95

2278:a2 24 20 8e 1d a9 01 d0 66

2280:0f c9 59 f0 04 c9 0d d0 2b

2288:e4 a9 40 a2 24 20 8e 1d b7

2290:60 80 40 20 10 08 04 02 d9

2298:01 7f cf df ef f7 fc fd 8c

22a0:fe 0d 20 12 20 20 43 48 1d

22a8:36 34 45 44 49 54 20 20 fd

22b0:0d 20 12 20 20 28 43 29 19

22b8:20 32 30 32 34 20 20 0d 32

22c0:20 12 20 20 44 41 56 49 bc

22c8:44 20 52 2e 20 20 0d 20 20

22d0:12 20 56 41 4e 20 57 41 e7

22d8:47 4e 45 52 20 0d 20 12 a9

22e0:20 44 41 56 45 56 57 2e 34

22e8:43 4f 4d 20 0d 13 20 20 63

22f0:20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 35

22f8:20 20 20 20 20 12 20 37 1c

2300:36 35 34 33 32 31 30 20 3f

2308:00 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 3e

2310:20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 56

2318:12 20 a3 a3 a3 a3 a3 a3 b4

2320:a3 a3 20 00 13 92 11 11 3b

2328:11 11 11 11 11 11 11 00 5d

2330:0d 00 12 40 2d 2b 2a 2f dc

2338:59 5a 58 43 56 0d 00 12 f9

2340:42 92 41 43 4b 20 12 52 f9

2348:92 4f 54 41 54 45 0d 00 1c

2350:12 4e 92 45 58 54 20 12 40

2358:4d 92 49 52 52 4f 52 0d b9

2360:00 12 3c 3e 5e 56 92 20 28

2368:12 46 92 4c 49 50 0d 00 06

2370:12 46 31 92 2d 12 46 38 17

2378:92 20 12 30 2d 39 0d 00 bd

2380:12 48 4f 4d 45 92 20 12 67

2388:43 4c 52 0d 00 12 52 56 e1

2390:53 92 20 20 12 53 50 41 ea

2398:43 45 0d 00 12 53 54 4f 49

23a0:50 92 20 12 53 92 41 56 96

23a8:45 0d 00 12 48 92 49 44 59

23b0:45 0d 00 92 20 20 20 20 e7

23b8:20 20 20 20 12 00 1d 1d 05

23c0:1d 1d 1d 1d 1d 1d 1d 1d 07

23c8:1d 1d 1d 1d 1d 12 00 92 1e

23d0:20 20 20 00 93 00 40 30 80

23d8:3a 46 4f 4e 54 2e 42 49 c5

23e0:4e 40 30 3a 46 4f 4e 54 68

23e8:2e 43 46 47 0d 0d 12 50 65

23f0:52 45 53 53 20 41 4e 59 4d

23f8:20 4b 45 59 0d 00 93 0d fc

2400:4c 4f 41 44 20 43 4f 4e a9

2408:46 49 47 55 52 41 54 49 8d

2410:4f 4e 20 28 59 2f 4e 29 67

2418:3f 20 12 59 92 9d 00 93 7e

2420:0d 53 41 56 45 20 43 4f d1

2428:4e 46 49 47 55 52 41 54 91

2430:49 4f 4e 20 28 59 2f 4e 10

2438:29 3f 20 12 59 92 9d 00 5a

2440:59 45 53 0d 00 4e 4f 0d a6

2448:00 0e 06 0e 0e 00 01 20 48

2450:a0 a0 01 00 0f 00 01 0b b6

2458:cf cf a0 05 00 00 00 05 e5

2460:05 20 2a a0 06 01 03 0f cb

2468:00 03 cf cf a0 00 0b 0c 8f

2470:0f 00 0e cf cf a0 0d 06 20

2478:08 07 02 04 cf cf a0 0b 11

2480:00 08 0f 08 09 20 a0 a0 d7

2488:0d 0b 0d 0c 00 04 20 a0 6d

2490:a0 00 01 0e 0f 0e 05 cf b4

2498:cf a0 0e 00 00 00 0b 06 ce

24a0:20 a0 a0 00 00 00 0e 00 51

24a8:01 20 a0 a0 20 2a cf cf b0

24b0:80 00 00 10 14 12 1e 00 5f

24b8:00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01